From Play to Practice: Growing into a Thought Partner

Images of Gee's Bend Heritage Trail via geesbend.org

by Ellen Sitkin

From a young age I was drawn to the Deep South. Perhaps because it felt far from where I came. I was captivated by the photos of William Christenberry, the quilts of Gee’s Bend, the writing of Ralph Ellison, the music of Ralph Stanley. Even the way the heat and humidity hung across the landscape felt mysterious and evocative.

I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the second child of two university librarians. My mother quilted with feminist neighbors and protested wars. My father, a weekend cyclist, read Seneca’s Epistulae Morales — in the original Latin — before bed. We lived in a cluttered, multi-level, open-plan house with books and artwork on every floor.

My grandparents enriched my upbringing: a meticulous electrical engineer, a sharp-witted New York City school gym teacher who lived to 106, a well-known Cuban artist and writer, and a German sculptor whose early death was blamed on the chemicals used in her work. In becoming artists, both my maternal grandparents broke with family tradition and set a path for me.

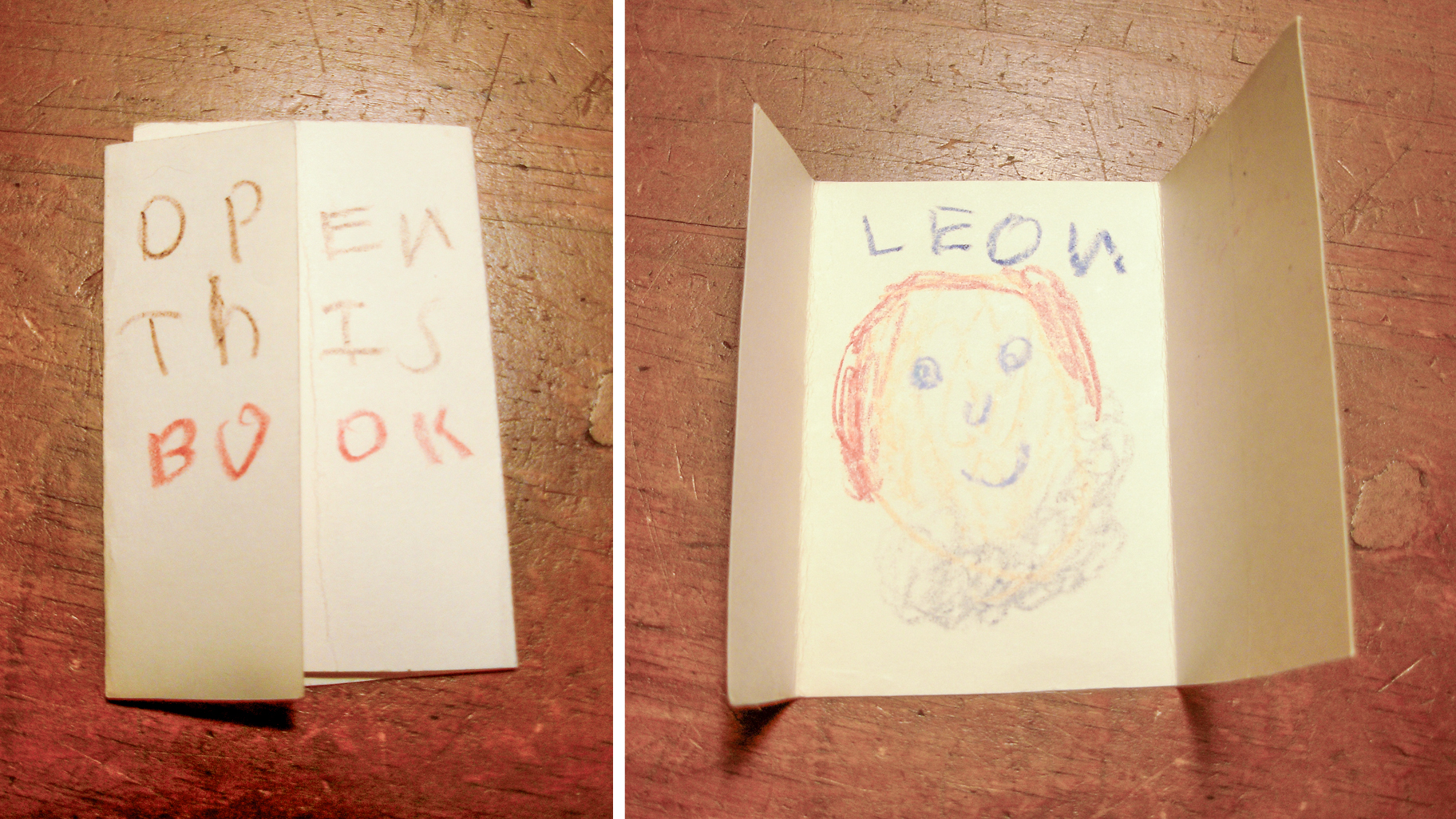

I gravitated toward design early in life. My first project was a gatefold card titled Open This Book, with a crayon portrait of my great-uncle Leon inside. I sketched fashion outfits and futuristic shopping malls with trampoline elevators. At 10, my friend Elizabeth and I sold handmade cards, pins, and earrings in our neighborhood — goofy, 1990s-styled concoctions, but people bought them. I took art classes throughout school, studied architecture and interior design books, memorized roof lines, and visited historic houses around the Northeast with my dad.

A summer class at the Boston Architectural Center introduced me to graphic design as a profession. Soon after, I found myself at the School of Art at Washington University in St. Louis, MO. The culture shock—from a hyper-competitive New England prep school to a warm, welcoming Midwest program — was a relief. I learned to typeset on a Heidelberg letterpress, cut paper with guillotine, and perfect-bind my thesis. The design process, I discovered, thrilled me more than the outcome — the research, the digressions, the dead ends, the “aha!” moments. While emphasizing the conceptual side of design, the most memorable advice from my thesis advisor was, “Sometimes you have to let the visual inform the concept.”

After college, I took jobs at the Brooklyn Public Library and the American Museum of Natural History. Yet, I found myself feeling like an imposter amongst the amoeba of hipsters fueling Brooklyn’s gentrification. I reasoned with myself: “My mom was born in Brooklyn Heights! My grandma taught gym class in Canarsie!” But I longed for something different, something more rooted in my own experience and connected to my curiosity about the Deep South.

That led me to Project M. A sort of Real World for socially-minded designers (minus the video cameras), it dropped eight of us into Greensboro, AL to immerse ourselves in the community and surface a need that could be addressed through design. We created Buy a Meter, a project that raised funds to help local residents access clean drinking water—ultimately one of Project M’s flagship efforts.

Though just a month long, Project M had a lasting impact on me, both personally and professionally. I made a lifelong friend, Wendy Smith, now a Thought Partner collaborator on brand strategy. I gained deep empathy for a community far from my own. And I stumbled into a process of research and collaboration I’d later understand as ‘Human-Centered Design.’ I later deepened that approach working at IDEO NY, where I honed my skills in process-driven, people-first work.

Jumping ahead two decades, I now live in New Orleans. After nearly 15 years in Brooklyn, my partner and I moved south in search of a better work-life-play balance for our family. I have found so much more. (More on that another time.)

In late 2019, soon after our move, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans put on a retrospective of William Christenberry’s work: Memory is a Strange Bell. Standing in the gallery, I thought about the path that brought me there — with too many late-night deadlines and too much tech startup chaos — to a new chapter in an incredibly vibrant and complex southern city.

Christenberry’s work, as the Ogden described it, “is both a celebration of all that the artist held sacred about his native South, and a condemnation of the worst parts of the culture.” That tension, between beauty, pain, and complexity, is what moves me most about a lot of southern art. It’s not slick or performative — it asks for honesty and depth.

That spirit shapes the work I do now. Thought Partner is grounded in clarity, emotional depth, and cultural context. That foundation was laid long before Thought Partner had a name. From childhood sketches to community-driven design, a thread has remained: a practice driven by curiosity, shaped by collaboration, and still evolving with each project.

© Ellen Sitkin